Tobacco use continues to be the leading cause of preventable disease and death in Canada. In 2017, more than 47,000 deaths were attributable to tobacco use in Canada, with an estimated $6.1 billion in direct health care costs and $12.3 billion in total overall costs.1 In November 2019, plain packaging regulations for tobacco products came into force as a part of Canada’s Tobacco Strategy, which aims to achieve a goal of less than 5% tobacco use by 2035.

Plain packaging has been adopted by a growing number of countries worldwide. As of July 2020, plain Canada cigarette packaging has been fully implemented at both the manufacturer and retail level in 14 countries: Australia(2012); France and the United Kingdom (2017); New Zealand, Norway, and Ireland (2018); Uruguay, and Thailand (2019); Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Israel, and Slovenia (January 2020); Canada (February 2020);and Singapore (July 2020). By January 2022, Belgium, Hungary, and the Netherlands will have fully implemented plain packaging.

This report summarizes evidence from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project on the effectiveness of plain packaging in Canada. Since 2002, the ITC Project has conducted longitudinal cohort surveys in 29 countries to evaluate the impact of key tobacco control policies of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). This report presents findings on the impact of plain packaging in Canada based on data collected from adult smokers before (2018) and after (2020) the introduction of plain Canada cigarette packaging. Data from Canada are also presented in context with data from up to 25 other ITC Project countries — including Australia, England, France, and New Zealand, where plain packaging has also been implemented.

Plain packaging substantially reduced pack appeal — 45% of smokers disliked the look of their cigarette pack after plain Canada cigarette packaging was introduced, compared to 29% before the law Unlik This report was prepared by the ITC Project at the University of Waterloo: Janet Chung-Hall, Pete Driezen, Eunice Ofeibea Indome, Gang Meng, Lorraine Craig, and Geoffrey T. Fong. We acknowledge comments from Cynthia Callard, Physicians for a Smoke-free Canada; Rob Cunningham, Canadian Cancer Society; and Francis Thompson, HealthBridge on drafts of this report. Graphic design and layout was provided by Sonya Lyon of Sentrik Graphic Solutions Inc. Thanks to Brigitte Meloche for providing French translation services; and toNadia Martin, ITC Project for French translation reviewing and editing. Funding for this report was provided by Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) Arrangement #2021-HQ-000058. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the viewsof Health Canada.

The ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey was supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute (P01 CA200512), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-148477), and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP 1106451).Additional support is provided to Geoffrey T. Fong by a Senior Investigator Grant from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research.

Regulatory authority for tobacco plain packaging (also known as standardized packaging) is provided under the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA)4, which had amendments adopted on May 23, 2018 as a legal framework to reduce the significant burden of tobacco-related death and disease in Canada. Plain Canada cigarette packaging aims to reduce the appeal of tobacco products and was introduced under the 2019 Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance)5 as one of a comprehensive suite of policies to help reach the target of less than 5% tobacco use by 2035 under Canada’s Tobacco Strategy.

The regulations apply to packaging for all tobacco products, including manufactured cigarettes, roll your own products (loose tobacco, tubes and rolling papers intended for use with tobacco), cigars and little cigars, pipe tobacco, smokeless tobacco, and heated tobacco products.E-cigarettes/vaping products are not covered under these regulations, since they are not classified as tobacco products under the TVPA.

4 Plain packaging for cigarettes, little cigars, tobacco products intended for use with devices, and all other tobacco products came into force at the manufacturer/importer level on November 9, 2019, with a 90-day transitional period for tobacco retailers to comply by February 7, 2020. Plain packaging for cigars came into force at the manufacturer/importer level on November 9, 2020,with a 180-day transitional period for tobacco retailers to comply by May 8, 2021.5, 8

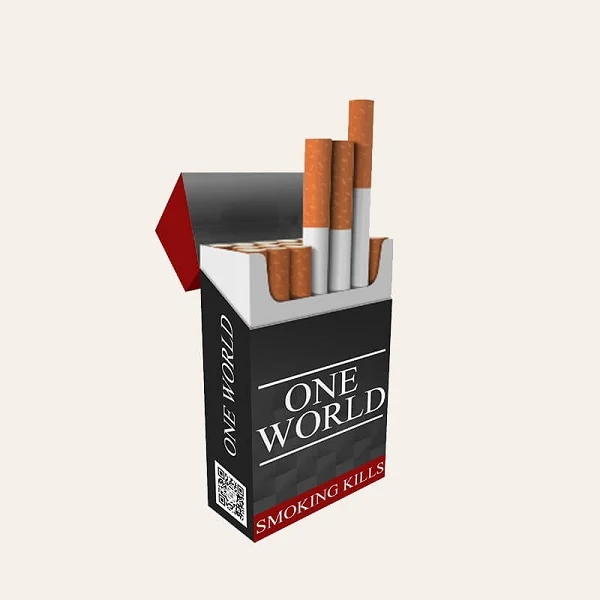

Canada cigarette packaging regulations have been referred to as the most comprehensive in the world, setting a number of global precedents (see Box 1). All tobacco product packages must have a standardized drab brown colour, with no distinctive and attractive features, and the display of permitted text in a standard location, font, colour, and size.Cigarette sticks cannot exceed specified dimensions for width and length; have any branding; and the butt end of the filter must be flat and cannot have recesses. Canada cigarette packaging will be standardized to a slide and shell format at the manufacturer/importer level as of November 9, 2021 (retailers have until February 7, 2022 to comply), thus banning packs with a flip top opening. Figure 1 depicts the slide and shell packaging with plain Canada cigarette packaging where a health information message is revealed on the back of the interior packaging when the pack is opened. Canada is the first country in the world to require slide and shell packaging AND was the first to require interior health messaging.

Canada cigarette packaging regulations are the strongest in the world and the first to:

• Ban the use of colour descriptors in all brand and variant names

• Require a slide and shell packaging format for cigarettes

• Require drab brown colour on the inside of packaging

• Ban cigarettes longer than 85mm

• Ban slim cigarettes of less than 7.65mm in diameter

Global precedents set by Canada’s plain packaging regulations

Canada did not implement new and larger pictorial health warnings (PHWs) on cigarette packs alongside plain packaging regulations, as required by other countries including Australia, the United Kingdom, France, and New Zealand. However, Canada’s cigarette pack warnings (75% of the front and back) will be the largest in the world in terms of total surface area when the mandatory slide and shell format comes into force in November 2021. Health Canada is finalizing plans to implement several sets of new health warnings for tobacco products that will be required to rotate after a specified period of time.9 Figure 2 presents the timeline to plain packaging in Canada in relation to the ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Surveys, which provide the data for this report.

This report presents data from the ITC Canada Smoking and Vaping Survey before and after plain packaging was fully implemented at the retail level on February 7, 2020. The ITC Canada Smoking and Vaping Survey, part of the larger ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, which was also conducted in parallel with cohort surveys in United States, Australia, and England, is a cohort survey conducted among adult smokers and vapers recruited from national web panels in each country. The 45-minute online survey included questions that were relevant to the evaluation of plain packaging, which have been used by the ITC Project to evaluate plain packaging in Australia, England, New Zealand, and France. The ITC Canada Smoking and Vaping Survey was conducted among a nationally representative sample of 4600 adult smokers whocompleted surveys in 2018 (before plain packaging), 2020 (after plain packaging), or in both years.Longitudinal data from Canada are compared with data from two other ITC countries (Australia and the United States) where similar surveys were conducted over the same time period, and which vary in the status of their tobacco packaging laws and requirements for changes in PHWs (see Table 1).i Characteristics of survey respondents in Canada, Australia, and the United States are summarized in Table 2. The report also presents cross-country comparisons of data on selected policy impact outcome measures in Canada and up to 25 other ITC countries.ii

Full details on the sampling and survey methods in each country are presented in the ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey

technical reports, available at: https://itcproject.org/methods/

The ITC Project has previously published reports on the impact of plain packaging in New Zealand18 and England19. Future ITC scientific papers will present more extensive analyses of the impact of plain packaging in Canada and other countries,as well as comparisons of policy impact across the full set of ITC countries that have implemented plain Canada cigarette packaging. Slight differences between the results reported for Canada in forthcoming scientific papers and the results reported in this document are due to differences in statistical adjustment methods, but do not change the overall pattern of findings.ii.

The 2020 results for Canada presented in the cross-country figures may vary slightly from the 2020 results in the longitudinal figures that are presented in this report because of differences in statistical adjustment methods for each type of analysis.iii

At the time of the post-plain packaging evaluation in Canada, most plain packs at retail were in flip top format, with slide and shell format available for only a limited number of brands One of the key objectives of plain packaging is to reduce the attractiveness and appeal of tobacco products.

Research conducted in different countries has consistently shown that plain cigarette packs are less appealing to smokers than branded packs.12-16

The ITC Survey showed that there was a significant increase in the percentage of Canadian smokers who found their cigarette pack“not at all appealing” after the implementation of Canada cigarette packaging. This significant decrease in appeal was in contrast to the two other comparison countries—Australia and the US—where there was no change in the percentage of smokers who found their cigarette pack “not at all appealing”.

There was a significant increase in the percentage of smokers who said they did not like the look of their cigarette pack after the implementation of plain packaging in Canada (from 29% in 2018 to 45% in 2020). Pack appeal was the lowest in Australia (where plain packaging had been implemented in combination with larger PHWs in 2012), with more than two-thirds of smokers reporting that they did not like the look of their pack in 2018 (71%) and 2020 (69%). In contrast, the percentage of smokers who said they did not like the look of their pack has remained low in the US (9% in 2018 and 12% in 2020), where warnings are text-only and plain packaging has not been implemented (see Figure 3).

These results are consistent with previous ITC Project findings showing an increase in the proportion of smokers who did not like the look of their pack after plain packaging was implemented in Australia (from 44% in 2012 to 82% in 2013)17, New Zealand (from 50% in 2016-17 to 75% in 2018)18, and England (from 16% in 2016 to 53% in 2018).19

The current findings also add to evidence from published studies showing significant reductions in pack appeal after implementation of plain packaging with larger PHWs in Australia20, 21 and the positive impact of Canada cigarette packaging on reducing pack appeal over and above increasing the size of PHWs in England.22

Another recent study evaluating the impact of plain packaging in the United Kingdom and Norway using established ITC survey measures provides further evidence that the implementation of plain packaging together with novel larger PHWs enhances warning salience and effectiveness beyond what can be achieved by implementing plain packaging without changes to health warnings. Prior to the implementation of plain packaging, both countries had the same health warnings on cigarette packs (43% text warning on front, 53% PHW on back).

After the implementation of plain packaging together with novel larger PHWs (65% of front and back) in the United Kingdom, there was a significant increase in smokers’ noticing, reading, and thinking about the warnings, thinking about the health risks of smoking, avoidant behaviours, forgoing cigarettes, and being more likely to quit because of the warnings.

In contrast, there was a significant decrease in noticing, reading, and looking closely at the warnings,thinking about health risks of smoking, and being more likely to quit because of the warnings among smokers in Norway, where plain packaging was implemented without any changes to health warnings.23 The different pattern of results seen in the United Kingdom compared to Norway demonstrates that Canada cigarette packaging enhances the effectiveness of large novel pictorial warnings, but cannot increase the impact of old text/pictorial warnings

Post time: Jun-15-2024